The University of Illinois System’s Institute of Government and Public Affairs (IGPA) is developing several Pandemic Stress Indicators, designed to evaluate the social and economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on Illinois residents. The Pandemic Stress Indicators grew out of the work on IGPA’s Task Force on the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic.

This first stress indicator is a frequent poll of three sets of experts about pandemic policies. Experts on economics, public health, and/or vulnerable populations from across Illinois have generously agreed to provide regular opinions on various pandemic policies. The panelists, with affiliations, are listed in the appendix.

Surveys were completed July 1-6, with 25 responses in total (11 experts in economics, seven in public health, and seven in vulnerable populations). In answering the surveys, all panelists provide only their own personal views,

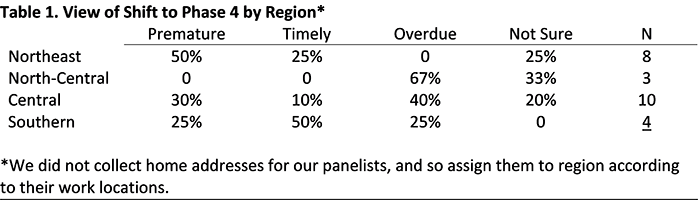

We asked respondents if the recent shift from Phase 3 (Recovery) to Phase 4 (Revitalization) in their region of the state was premature, timely, or overdue. The relatively small number of respondents, particularly for the north-central and southern regions, make comparison a bit risky, but experts in the Chicago area seem warier of relaxed rules having been introduced too early, while the experts in the center of the state were more likely to see the shift as overdue. We did not collect home addresses for our panelists, and so they are assigned to a region according to their work locations.

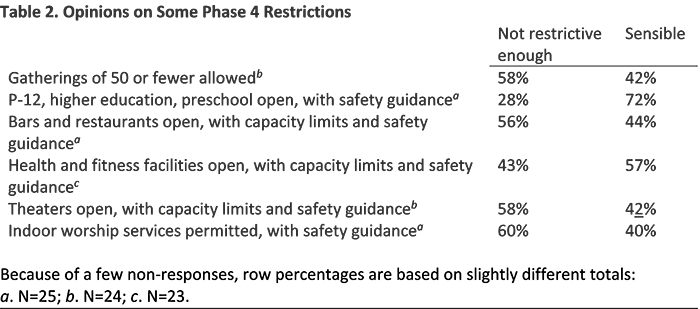

As we did with the shift from Phase 2 to Phase 3, we asked the experts to opine on some of the restrictions in place for Phase 4. Are they sensible, too restrictive, or not restrictive enough? No respondent found any of the rules too restrictive, but there was some division on whether they were reasonable or too lax.

About a month ago, in the second wave of this panel, the shift to allowing indoor worship services struck 77% of our respondents as not sufficiently restrictive, and stood apart from six other rules that were then seen as sensible by large majorities. In this wave, disapproval for the permission of religious services is a bit lower and comparable to reactions to most of the changes. The outlier, instead, is re-opening of schools, preschools and universities—a change that is not actually being implemented just yet in most cases because of summer breaks. Roughly three-quarters of respondents found this shift sensible, while they were mainly nervous that the other openings (with guidance) were risky.

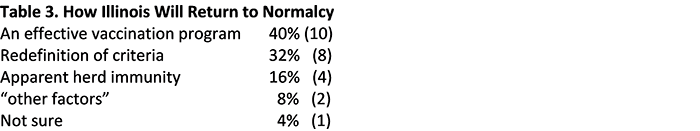

Looking ahead to the shift out of restrictions and back to normal life, we set aside the question of when parts of the state might shift to Phase 5, and asked how the shift will take place.

“The shift from Phase 4 (Revitalization) to Phase 5 (Illinois Restored) is presently described as depending on ‘Vaccine, effective and widely available treatment, OR the elimination of new cases over a sustained period of time through herd immunity or other factors’ (emphasis added). Do you think that when parts of Illinois are reclassified to Phase 5 it will be because of...”

Revising the criteria for moving from one phase to the next played a role in the most recent shift, from Phase 3 to Phase 4, as requirements for contact tracing were quietly set aside. Just the same, the most popular answer was not that the criteria would adjust over time, but that Phase 5 will come only with a vaccine.

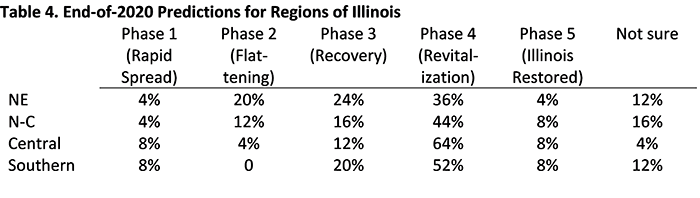

We asked the experts to forecast about six months out, by telling us their best guess for what classification each of the state’s four regions will have at the end of 2020.

While the most popular prediction for all regions was the status-quo (i.e. still in Phase 4), there was also substantial pessimism about shifting backwards. Those respondents who foresee parts of the state being classified as “restored” are almost exactly matched by those who expect some regions to be all the way back to Phase 1 (“Rapid Spread”) at year’s end.

Note too that nobody who said that Phase 5 would arrive following a vaccination program on the prior question went on to predict any region being in Phase 5 at year’s end. The few optimists predicting Phase 5 anywhere in the state by late December were mainly those who also foresee Phase 5 declarations following from changed criteria. It is possible, therefore, that the prediction of Phase 5 should be seen less as optimism about the pandemic fading than cynicism about political pressures to assert that it has faded.

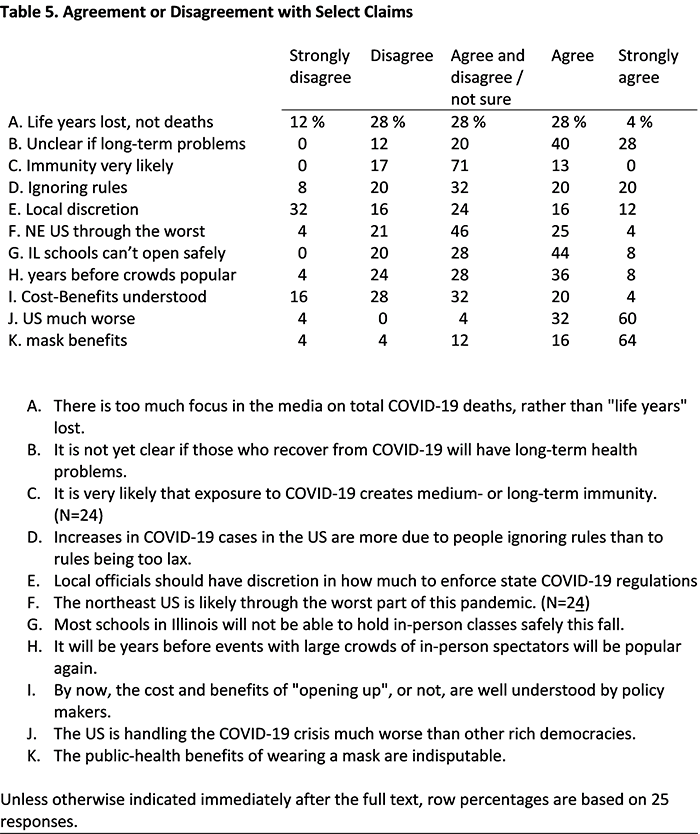

We also offered respondents a series of claims or contentions sometimes heard in discussions and debates about policy, asking for an agree/disagree reaction. Table 5 shows responses, with abbreviations for the topic. The full, precise text for each claim (row) is immediately below the table.

The claims were randomly ordered in the survey, and the order in Table 5 is arbitrary. If one attempts to order them by degree of consensus, the “winner” is probably that the US is handling the COVID-19 crisis badly, by comparison to “other rich democracies” (item J). There was, likewise, almost unanimity that there are indisputable benefits from wearing masks (in public) (item K). The only other row with more than half of the responses in one column is a different kind of consensus, not to agreement or disagreement, but, rather, to uncertainty.

The question of whether exposure to COVID-19 creates “medium- or long-term immunity” (item C) is central to the prospect of “herd immunity.” But the suggestion that immunity is “very likely” pushed 71 percent of respondents into the uncertain or ambivalent response (six both agree and disagree, and 11 not sure).

Just over half of the respondents agreed or agreed strongly that “Most schools in Illinois will not be able to hold in-person classes safely this fall.” Our wording was perhaps ill-chosen, alas, because that agreement could indicate an expectation of safe (though quite possibly inferior) online schooling at most schools. Or, in a very different eventuality, agreement could follow from an expectation of unsafe (and unwise) in-person schooling being the norm.

At the other end of the spectrum, respondents were sharply divided on whether local officials ought to have discretion in implementing restrictions (item E). That dispersion was evident within each expert group too. Similarly, item A saw a roughly equal agree/disagree split with lots of middle responses. But, by contrast with E, A separated economists from public health and vulnerable-population experts. “Life years lost” is a measure that takes account of not only the fatality count but also the age of those who die. When a disease is particularly hard on the elderly, rather than claiming the lives of young and old alike, it can look much less disastrous in the metric of life-years-lost than it does in the simpler metric of total deaths. It transpires that in our small panel, economists are much more enamored of this statistic.

Five of the 11 economists agreed (one strongly) that the media ought to discuss life-years-lost more and deaths less. None strongly disagreed. Meanwhile, only three of the 14 others agreed (none strongly), and two strongly disagreed. Yet again, however, there is potential ambiguity, as one might disagree with the claim because (s)he thinks deaths are the right statistic for media reports, or because (s)he thinks the media does not neglect discussing life years lost, in contrast to the wording of the claim.

We concluded the survey by inviting the experts to go beyond assessing our small battery of contentions, by telling us If there are “particular arguments about the pandemic and pandemic policies that you think are important and correct but under-emphasized or misunderstood, or incorrect, but widely believed.”

Some respondents emphasized education, noting that the public has not been well enough instructed in how to use masks or in why contact tracing is imperative. One complained that “the use of masks has become over-politicized.” Another respondent was bleak, noting that present-day “expectations are not in-line with what infectious disease experts know—we are in the first mile of a marathon."

Appendix

All regions of Illinois have now shifted to Phase 4 (Revitalization) under the Restore Illinois plan. The June 26 transition was based on data pertaining to COVID-19 cases and medical capacity, plus testing and tracking capacity, though contract tracing criteria (90 percent of cases in region monitored within 24 hours of diagnosis) are now being treated as a goal rather than a strict requirement. Do you think this shift in your region was:

Below are some of the revised restrictions on life now in place for Phase 4. How would you characterize each rule? If you are not sure what to think about a given rule, you can leave a row blank. [Response options for each row were: “too restrictive”; “sensible”; and “not restrictive enough”. Non-response was also permitted.

Gatherings of 50 or fewer allowed

P-12, higher education, preschool open, with safety guidance

Bars and restaurants open, with capacity limits and safety guidance

Health and fitness facilities open, with capacity limits and safety guidance

Theaters open, with capacity limits and safety guidance

Indoor worship services permitted, with safety guidance

The shift from Phase 4 (Revitalization) to Phase 5 (Illinois Restored) is presently described as depending on "Vaccine, effective and widely available treatment, OR the elimination of new cases over a sustained period of time through herd immunity or other factors" (emphasis added). Do you think that when parts of Illinois are reclassified to Phase 5 it will be because of...

What is your best guess of how each of the regions in Illinois will be classified at the end of 2020? If you're comfortable guessing only about select regions, feel free to leave rows blank.

| Phase 1 (Rapid Spread) | Phase 2 (Flattening) | Phase 3 (Recovery) | Phase 4 (Revitalization) | Phase 5 (Illinois Restored) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northeast | |||||

| North-Central | |||||

| Central | |||||

| Southern |

Below are some claims sometimes made in discussions and debates about the pandemic and policies aimed to control it. Please indicate for each how you react.

[Response options were: “strongly agree”; “agree”; “agree somewhat, disagree somewhat”; “disagree”; “strongly disagree”; and “I’m not sure”. Non-response was also permitted.]

[order randomized]

There is too much focus in the media on total COVID-19 deaths, rather than "life years" lost.

It is not yet clear if those who recover from COVID-19 will have long-term health problems.

It is very likely that exposure to COVID-19 creates medium- or long-term immunity.

Increases in COVID-19 cases in the US are more due to people ignoring rules than to rules being too lax.

Local officials should have discretion in how much to enforce state COVID-19 regulations

The northeast US is likely through the worst part of this pandemic.

Most schools in Illinois will not be able to hold in-person classes safely this fall.

It will be years before events with large crowds of in-person spectators will be popular again.

By now, the cost and benefits of "opening up", or not, are well understood by policy makers.

The US is handling the COVID-19 crisis much worse than other rich democracies.

The public-health benefits of wearing a mask are indisputable.

As usual, we would also like to provide you the chance to elaborate on questions above. Are there particular arguments about the pandemic and pandemic policies that you think are important and correct but under-emphasized or misunderstood, or incorrect, but widely believed?

Experts in Pandemic Stress Indicator Panel

Evan Anderson, Northern Illinois University

Laurence Appel, University of Illinois at Chicago

Brandi Barnes, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Mark Daniel Bernhardt, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Mark Borgschulte, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Stephen Brown, University of Illinois at Chicago

Beverly Bunch, University of Illinois at Springfield

Patricia Byrnes, University of Illinois at Springfield

Lorraine Conroy, University of Illinois at Chicago

Toni Corona, Madison County Health Department

Michael Fagan, Northwestern University

Joseph M. Feinglass, Northwestern University

Barbara Fiese, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Lidia Filus, Northeastern Illinois University

Tamara Fuller, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Michael Gelder, Northwestern University

Robert J. Gordon, Northwestern University

Betsy Goulet, University of Illinois at Springfield

Jeremy Groves, Northern Illinois University

Bart Hagston, Jackson County Health Department

Marc D. Hayford, Loyola University Chicago

Ronald Hershow, University of Illinois at Chicago

Hana Hinkle, University of Illinois at Chicago

Joseph K. Hoereth, University of Illinois at Chicago

Wiley Jenkins, Southern Illinois University

Timothy Johnson, University of Illinois at Chicago

Greg Kaplan, University of Chicago

Sage J. Kim, University of Illinois at Chicago

Brenda Davis Koester, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Ken Kriz, University of Illinois at Springfield

Janet Liechty, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Justin McDaniel, Southern Illinois University Carbondale

Ruby Mendenhall, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Edward Mensah, University of Illinois at Chicago

Linda Rae Murray, University of Illinois at Chicago

Katie Parrish, Lake Land College

Sarah Patrick, Southern Illinois University Carbondale

Alicia Plemmons, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville

Carolyn A. Pointer, Southern Illinois University

Tara Powell, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Tyler Power, Quad Cities Chamber of Commerce

Elizabeth Powers, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Chris Setti, Greater Peoria Economic Development Council

Abigail Silva, Loyola University Chicago

Brian Smith, University of Illinois at Springfield

Tracey J. Smith, Southern Illinois University Springfield

Nicole M. Summers-Gabr, Southern Illinois University

Vidya Sundareshan, Southern Illinois University

James A. Swartz, University of Illinois at Chicago

Kevin Sylwester, Southern Illinois University Carbondale

Karriem Watson, University of Illinois at Chicago

Moheeb Zidan, Knox College

Looking ahead to the shift out of restrictions and back to normal life, we set aside the question of when parts of the state might shift to Phase 5, and asked how the shift will take place.